|

We don’t have to sit on the ground and read Ortega y Gasset’s Meditations on Hunting to each other, but in today’s politically correct, urbanized and computerized world we need to understand what we are doing, and why – and convey some of that as part of the story we tell.

“So you have to tell a story. Big deal. You’re still out hunting.”

No, you’re not. You’re filming a television show, and the bulk of your time afield must be spent filming the elements that make the story – elements that have nothing to do with hunting. Television is a visual medium and much of the Who, What, Where, Why and When of journalism must be conveyed visually.

This is the necessary footage of stalking, walking from one area to another, driving from one area to another, getting in and out of the vehicle. You need close-ups of hunters glassing, close-ups of rifles being loaded and unloaded, beauty shots of pertinent scenery and the lodge, establishing shots so that the viewer can orient himself, and footage of game animals near and far. Add to that the discussion and rating of game (too small, too young, broken tines, whatever), the conversations between hunters, between hunter and guide – all the constants of hunting that are the same everywhere and also new and different each time.

It must all be filmed, and it takes time.

While you’re doing this, you keep glassing and looking for the right animal, but once it has been found, it can only be taken if and when the cameraman says so. This can lead to levels of frustration you have never imagined.

When that new world record you have been dreaming of for the last 30 years unexpectedly trots out in front of you 75 yards away, and the outfitter, on the verge of coronary arrest, says, “Take him. Take him! TAKE HIM!” it’s a hard thing to wait calmly for the cameraman to get his camera set up, in focus, rolling, and framed, as your dream drifts off into the woods, vanishing forever.

But if the camera doesn’t see it, there is no show, so you cannot shoot. I have had this happen.

Perhaps you’ve done everything right, stalked and glassed and tracked from dawn to dusk for many days and now at the last minute of the last day, there he is, within range, broadside, waiting. Then the cameraman says, “There isn’t enough to light to film.”

You cannot shoot. I have had this happen – and I thought that outfitter might murder me or the cameraman or both.

Finding the stag was relatively quick and easy, but finding a stag and getting close enough to shoot it are two different things. Jim spotted the animal early one morning in a ravine where both light and wind were against us. By the time we had hot-footed it back to the truck, driven around a mountain, and hiked up a long brush-filled draw, the stag had moved into a thicket where a shot was impossible. He stood there gazing serenely at us while we gazed back at him considerably less serenely.

It was a long wait before that stag eventually moved into a more open area. During that time, Mike kept up a constant whispered monologue of footage we would need to get if the stag moved uphill into the sun versus what we would need if he moved downhill in the shade. He also suggested what questions I should ask Jim to provide information that would interest and intrigue the viewers and suggested to Jim the kind of information American viewers would want to know. This was interspersed with steady reminders to me not to shoot until Chris gave the OK.

I had never hunted red stag before and this was a magnificent specimen. By the time he finally moved and I heard Chris whisper, “Any time,” I was more nervous and eager than I’ve been since I kissed beautiful Susan Crampton in the back seat of my father’s Rambler 40 years ago.

Fortunately, I was using shooting sticks, and H-S Precision builds a dazzlingly accurate rifle.

The fallow buck was more difficult. Glenroy Lodge is a very luxurious establishment with excellent cuisine. The only reason I didn’t come away from there looking like the Pillsbury dough-boy was the unsuccessful stalks up one mountain after another as fallow bucks made monkeys out of us.

When we did finally take a buck it was, as so often happens in hunting, almost by accident. We were working our way down a slope after yet another unsuccessful stalk when a buck burst out of the brush below us. Only Chris and I saw it, and neither of us was a competent judge of quality. Nevertheless, Jim trusted us enough to set up a complicated combination of stalk and drive, with Mike demoted from field producer to beater.

Making a long shot – more than 200 yards – at a running animal is never easy with a camera whirring softly by your right ear. Along with this, you have the added pressure of knowing that if you goof it up you will have to bribe the cameraman heavily or several million viewers will know you made an ass of yourself. Fortunately, shooting sticks and the H-S Precision helped me do my job, and Chris had to make do with his normal salary.

By the way, if there is anyone out there who really believes the reverses are filmed during the actual hunting, as opposed to set up afterward, please contact me. I have some investment opportunities I would like to discuss with you.

So it’s not hunting. It’s telling a story about a hunt, which is a very different thing.

“OK, but it’s still a lot of fun, and it’s the kind of thing anyone could do, given half a chance.”

It is a lot of fun. Filming Simon & Simon was a lot of fun – I have never laughed so much or so hard in my life – even at 70 hours a week. Most people find ways to make their work enjoyable. You come home and tell the wife how hard you worked, how exhausted you are, what a jerk your boss is, and it may all be true, but for the most part, most of us enjoy what we do.

When we weren’t looking for trophies, hunting them, filming them before and during the hunt, filming recreations of the stalk and the reverse shots, filming the appropriate discussions and conversations about each animal, we spent our time filming the essential Who, What, Where, Why, and When.

We filmed Himalayan tahr, chamois, feral sheep, feral goats, wapiti, bison, wild turkeys (Merriam’s), as well as the extraordinary beauty that is New Zealand. We filmed the lodge, inside and out. We interviewed Jim at length. We drove around the area and filmed local tourist attractions, historic towns, and more incomparable beauty.

We filmed a promo of Mike bungee-jumping. We tried to record the sounds of red stag in the roar, and the peculiar love-song (think of an angry bullfrog) of the rutting fallow buck. We drove and walked up and down mountains and crawled through nightmare tangles of briar rose and mathaguary with thorns like industrial sewing needles. We laughed so much our stomach muscles ached. It was seven days of pure, unadulterated fun. It was also work.

“But anyone could do it.”

There are three ways a hunting show can get information to the viewer. A narrator can give the information directly. The host can give the information directly while on camera. Or, the host can engage the guide – or landowner or hunter or some expert brought on board for the occasion – in conversation. Most shows use a combination of the three techniques, but on-camera information is preferable and usually more effective. Instead of being lectured, the viewer is drawn into a conversation between two knowledgeable people. And there’s the rub.

There is something about the camera that can cause certain people to clam up with nerves. Off-camera they may be exciting, vivacious, fascinating, witty, and packed with pertinent information, but something about the camera freezes them drier than a day-old pretzel. This is when the host earns his money. He has to have the ability to get the guest so involved in the subject at hand that he forgets about the camera, or the host has to be so knowledgeable that he can fill in for what the resident expert is too camera-shy to say.

While he is doing all this, the host must always keep in mind the story he is trying to tell, determining constantly, on the spur of the moment, which elements will contribute to the story and need to be discussed and filmed.

Unseen, unsung, unnamed in the credits, the cameraman is the most important person involved in an outdoor show. Think of your favorite hunting show. Think of the photography on that show, those spectacular, breathtaking shots of whitetails tiptoeing through the woods, bugling elk with clouds of white vapor streaming from their nostrils in the frosty air, pronghorns coming in to drink from a stock tank on a barren plain. The technical skill involved in getting those shots is incomparable, but more than that, if the shot is clear and steady, it means that cameraman was relatively close.

Good cameramen routinely manage to stay with the host and guide to get within easy rifle range without spooking the animal, and they do it while carrying a 30-pound, $25,000 – $95,000 camera, a tripod, extra lenses, spare camera batteries, spare sound batteries, lens-cleaner, camouflage tarps or netting, plus their personal gear – more weight, in short, than you or your guide would ever dream of carrying. There’s a reason why outdoor cameramen are young and stronger than bulls.

At the end of that week, I flew home. Mike and Chris went on to another location on the other side of the island for two more weeks of filming. To get 23 episodes on the air, Mike will spend five months on the road and another five months in the office working on the endless ancillary details that are part and parcel of any outdoor show. This includes sponsorship, setting up future hunts, travel arrangements and logistics – all the critical and boring minutiae that must be done before he can go out on the road again.

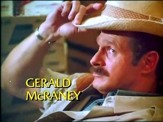

He will spend endless hours trying to line up interesting celebrity guests viewers will enjoy seeing. (Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf; my erstwhile brother on Simon & Simon, Gerald McRaney; and professional bull riding champion Tony Mendes have already appeared on shows.) And he will spend an inordinate amount of time scrambling to replace celebrities whose unpredictable careers force them to cancel at the last minute. In short, he will spend five months combining stress and boredom in equal amounts so that he can spend another five months having fun while working his tail off..

|